The empress Messalina is one of the riskiest lady in Roman history. She was Claudius’ third wife and is known today as the nymphomaniac empress, the most promiscuous lady in all of Rome. In popular culture, the Messalina represents the height of unrestrained, violent, irrational, and impulsive behavior. Her goals are exceedingly evil, and her sexual appetite is unmatched. In The Master and Margarita, Mikhail Bulgakov invited Messalina as a guest to Satan’s ball. When describing the insane wife in the attic in Jane Eyre, Charlotte Brontë compared her to Messalina and a German vampire.

1. Noble beginnings

When Valeria Messalina wed Tiberius Claudius Nero Germanicus in 38 A.D., she was at most 18 years old. Contrarily, Claudius was a 47-year-old father of two who had been through two divorces. The two were first cousins at a distance because they were both descended from Octavia, the sister of the Divine Augustus.

Because that Messalina was more prestigious than Claudius’ prior wives, getting married to her was a huge honor for him. His belated entrance into public life was accompanied by his marriage to an Octavia descendent, which served as proof that the new emperor—his nephew Caligula—approved of him and was attaching him tightly to the line of succession.

The marriage, however, was probably less exciting for Messalina. Her new spouse had lived his entire life as a source of shame for the family. Due to his apparent impairments, his mother supposedly called him a monster, his great-uncle Augustus forbade him from sitting with the family in public, and his uncle Tiberius forbade him from holding any public post. Nobody was more aware of how unwelcoming Imperial Rome was to people with disabilities than Claudius. He had witnessed his siblings marrying well and being given glorious accolades. Claudius didn’t have much of a reputation and only contributed his bloodline to Messalina’s lineage.

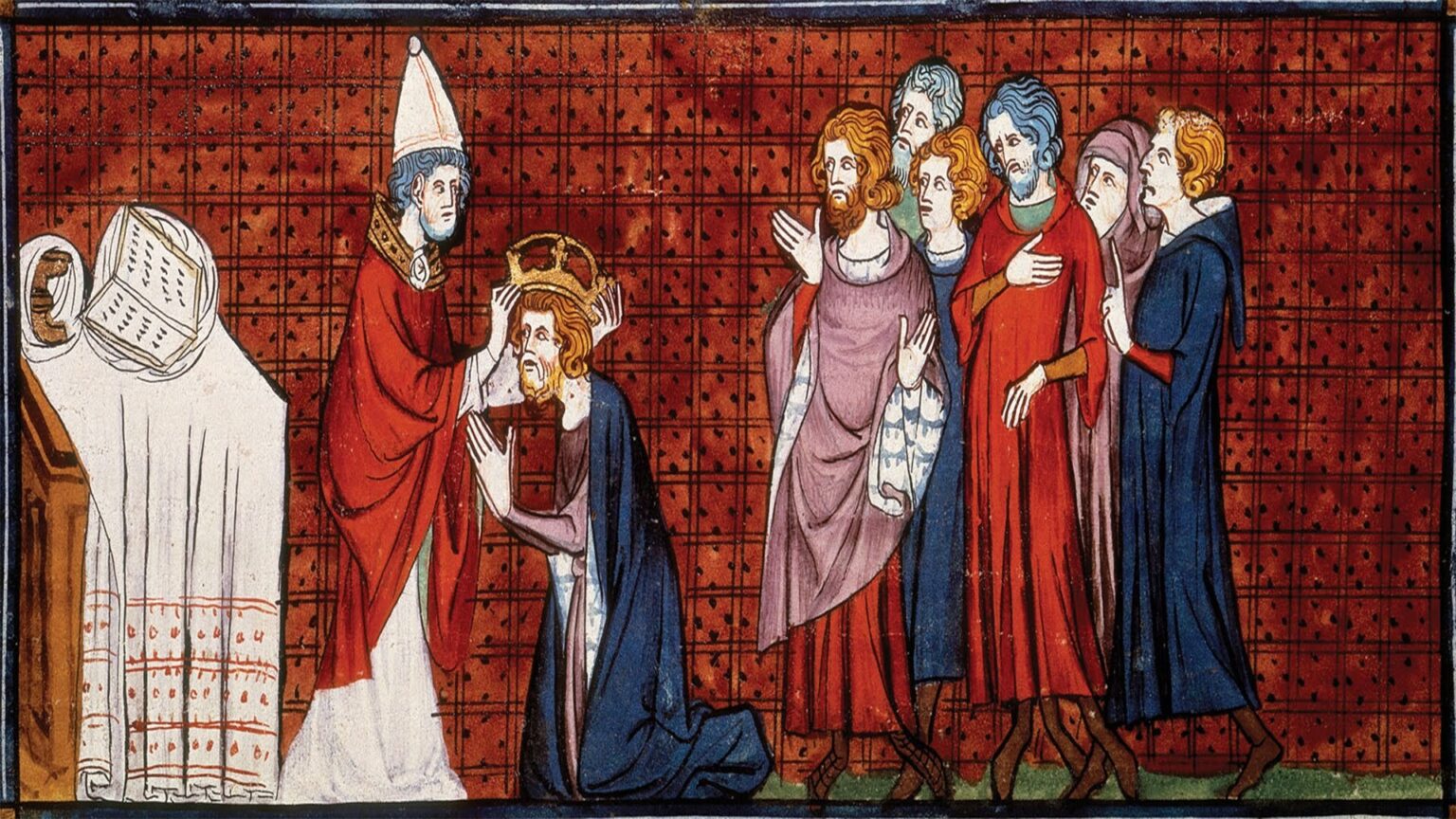

2. POWER TRANSFER

In a short period of time, the couple produced two children, and Claudius unexpectedly—and divisively—became emperor. After Caligula was killed in AD 41, Claudius sought sanctuary in the army barracks and argued with the Senate for two days to get them to recognize him as emperor.

With no prior experience and little promise, Messalina’s husband had far exceeded everyone’s expectations when he assumed control. Messalina had risen to the position of empress while she was still in her early 20s and ready for a life of aristocratic leisure. She made history when she gave birth to the first son of a Roman emperor just a few weeks after her husband assumed the throne.

3. Messalina’s reputation

The first and second century A.D. authors Tacitus and Suetonius, who both wrote centuries after Messalina’s passing and at a time when Rome’s first emperors were under fire, provide the majority of information on their connection. The Twelve Caesars contains descriptions of the duo from Suetonius, but they are brief and straightforward. Tacitus had a lot more to say about it.

These writings do not cover Messalina’s early years as Claudius’s wife and empress, thus it is uncertain if her renown existed from the outset of her husband’s tenure. Roman men typically believed that women were naturally corrupt, as opposed to men, who underwent corruption. Roman law disregarded women’s ability to manage their own property and treated them like eternal juveniles.

Thoughts towards Messalina may have evolved with time, as Tacitus’ account begins in A.D. 47, six years into Claudius’ rule, the historian believes Messalina to be a monster. The empress is initially mentioned by Tacitus as having used her husband to exact revenge on Valerius Asiaticus and Poppaea Sabina, two of her personal foes. Messalina coveted Asiaticus’s beautiful Gardens of Lucullus, which he owned. She spread allegations that Poppaea and Asiaticus were having an illicit relationship (who had taken a lover Messalina desired for herself). The two were detained by Claudius, and Asiaticus was slain. Poppaea was imprisoned, and according to Tacitus, after being repeatedly harassed by Messalina’s spies, she committed suicide.

According to Tacitus, Messalina routinely utilizes the legal system and government services for her own personal gain. She exacts revenge through them on people who offend her, turn down her approaches sexually, or make her envious. She banishes family members and kills opponents. She fabricates omens and spreads stories to manipulate her spouse into doing what she wants. She politicizes the personal.

4. Marriage and betrayal

In the end, Messalina’s actions brought her down. Roman historians joyfully and sarcastically recorded her undoing and subsequent murder. The primary source of knowledge about Messalina’s final scandal is once more Tacitus. The Roman poet Juvenal, who authored his Satires in the late first or early second century A.D., also repeated the tale of Messalina and delivered a harsh denunciation of her. Messalina was still portrayed as a villain by Cassius Dio, a Roman historian, who wrote a century later, referring to her as “the most abandoned and insatiable of women.”

When Messalina establishes a relationship with Senator Gaius Silius in A.D. 48, the episode officially begins. Several sources portray Silius’ complicity differently; in Juvenal and Dio, he is a passive target of her power, whereas in Tacitus, he is an active participant. He receives opulent gifts from Messalina, including homes and family heirlooms. They continue having an affair until it is revealed to the public. Messalina is stuck with her imperial husband even after Silius divorces his wife.

Whether true or false, rumors of their wedding party swiftly reach Claudius in Ostia. His administrators send his two favorite mistresses to deliver the news that his wife has publicly divorced him by getting married to someone else. According to Tacitus, Claudius becomes terrified because he thinks Messalina and Silius are trying to overthrow him. Claudius has them detained right away. Messalina is escorted by guards to the Gardens of Lucullus, while Claudius is presented with Silius at the army camps. Silius and his accomplices are immediately put to death for treason, after which Silius’s name is forgotten in history.

5. Death of an empress

About Messalina’s destiny, Claudius hesitates. She has been his wife for ten years, is the mother of his children, and is a lady he genuinely loves. He softens and chooses to hear her out the following day. Supporters of Claudius take action because they are concerned Messalina will get away with it. They misinform Roman centurions and a tribune that Messalina is to be put to death in the gardens at the emperor’s command.

Messalina is with her mother in the gardens. Messalina reportedly persists despite being trapped, according to Tacitus. She makes several unsuccessful attempts to escape the predicament. She is given the chance to commit suicide when the soldiers show up, but she is unable to do so. She was so devoid of virtue, sneers Tacitus, that she couldn’t even commit suicide. She is fatally wounded by one of the tribunes.

Claudius is said to be unfazed by the news of the passing of his wife, according to Tacitus: “[H]e called for a cup and went through the ritual of the meal. He displayed no signs of hate, joy, wrath, despair, or, in general, any other human feeling even in the days that followed. A damnatio memoriae against Messalina is enacted by the Roman government, which removes her name from all public and private spaces and defaces her sculptures. Yet, Messalina’s memory did not vanish as a result of this official erasure. Instead, her bigamous marriage and sexual desires led to stories, jokes, and gossip that would eclipse all of her other historical actions, even her political intrigues.